|

(

14

)

|

Date

|

Start time

|

End time

|

Event name

|

Event description

|

Location

|

Cost

|

Website link

|

Event contact phone

|

Event contact email

|

Category (Maximum of 4 categories)

|

Terms and conditions

|

Name

|

Email

|

Phone

| |

|---|

| 1. |

Saturday 18 May 2024

2024-05-18T00:00:00+10:00

|

8:00am

|

2:00pm

|

Rainforest Rescue Annual Community Tree Planting Day

|

Rainforest Rescue’s 2024 Annual Community Tree Planting Day is scheduled for Saturday 18 May 2024 and you’re invited!

If you've not attended a tree planting before, it's an enjoyable way to get outside, give back to nature and meet likeminded people in the local community.

2024 also marks our 25th anniversary, and we’re so excited to celebrate with you.

Make sure you don’t miss this planting… we have a feeling it’ll be a record-breaker!

“The better time to plant a tree was 25 years ago, the best time is now”.

The event will commence at 8:00 am, so we will be finished planting before noon (before it gets too hot).

After a morning of planting trees to restore rainforest and connectivity, you’re invited to remain on site and celebrate 25 years of Rainforest Rescue with us.

Join us!

|

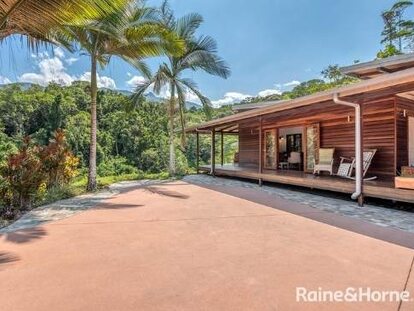

NightWings Rainforest Centre, 2125 Mossman Daintree Road, Wonga, Qld

|

Free

|

https://www.rainforestrescue.org.au/2024-planting/

| |

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Family Event, Free Event, Senior Event

|

Health and Safety

As always, the health and safety of our staff, supporters, and the communities in which we work are of utmost importance to us.

We ask that all attendees register for a free ticket via Humanitix.

Please ensure you dress appropriately for the event (e.g., sun-safe clothing, hat, sturdy closed-toed boots/shoes). Don’t forget to bring your water bottle and stay hydrated throughout the day

If you are feeling unwell or have recently been unwell please do not attend the planting. We thank you for considering the health and safety of others

We’re looking forward to putting trees back on the land with you and celebrating our 25th anniversary. See you in the Daintree!

|

Mark Cox

|

[email protected]

|

0414 547800

| |

| 2. |

Sunday 9 June 2024

2024-06-09T00:00:00+10:00

|

9 am

|

1 pm

|

WHOLESOME ONE DAY WELLNESS RETREAT

|

Immerse yourself in a day of self-care and connection.

Nourishing Retreat nestled in Luxurious Tropical Resort ~ Niramaya Day Spa, Port Douglas.

Retreat is designed to help you take some time for yourself to Reconnect and Recharge.

Retreat Schedule:

Welcoming Circle

Guided Yoga Class

Breath Work

Sauna and Plunge Pool Session

Letting Go Fire Ceremony and Closing Circle

Wholesome Lunch (drinks not included)

Swim, Relaxation, Journaling optional

|

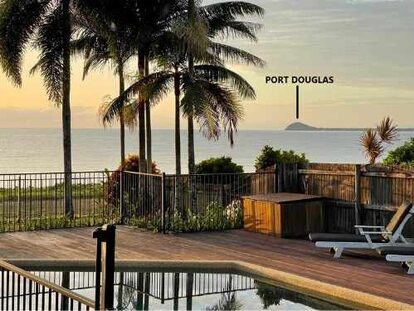

Niramaya Day Spa, Port Douglas

|

125

|

https://yogainthetropics.com/june-9th

|

+61438117486

|

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Sport Event, Workshop or Training

| |

Petra

|

[email protected]

|

0438117486

| |

| 3. |

Saturday 18 May 2024

2024-05-18T00:00:00+10:00

|

5:30PM

|

9:30PM

|

Italian Feast Under the Stars with Live Opera

|

Join us for the Carnivale edition of Sheraton’s ‘Italian Harvest Feast’. This exclusive outdoor dining experience celebrates the start of the harvest season through fine food and wine, spectacular Italian opera performances and local storytelling. Enjoy a cocktail on arrival, followed by a four course Italian feast with paired wines

|

Sheraton Grand Mirage Resort Port Douglas

|

$169

|

https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/italian-harvest-feast-long-table-dinner-under-the-stars-tickets-876409342937?aff=Newsport

| | |

Food & Wine Event

| |

Alina

|

[email protected]

|

0413357035

| |

| 4. |

Sunday 5 May 2024

2024-05-05T00:00:00+10:00

|

1PM

|

5PM

|

MONTHLY $20 ALL YOU CAN EAT BBQ At The Yachty

|

MONTHLY $20 ALL YOU CAN EAT BBQ At The Yachty

KIDS EAT FREE

|

Port Douglas Yacht Club

|

$20 all you can EAT - KIDS EAT FREE

| |

0419009425

|

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Family Event, Food & Wine Event, Live Entertainment

| |

Bruce Dargavel

|

[email protected]

|

0419009425

| |

| 5. |

Friday 3 May 2024

2024-05-03T00:00:00+10:00

|

7.00

|

Late

|

THE RUBENS - BLACK BALLOON TOUR

|

Live concert by award winning alternative rock band, The Rubens

|

Port Douglas Yacht Club

|

$55

| |

0419009425

|

[email protected]

|

Live Entertainment

|

BOOK TICKETS AT OZTIX

|

Bruce Dargavel

|

[email protected]

|

0419009425

| |

| 6. |

Saturday 25 May 2024

2024-05-25T00:00:00+10:00

|

4PM

|

8PM

|

Sheraton Sunset Sessions x Cafe Del Mar

|

Gather for an unforgettable evening in Australia’s most iconic pool during this special Carnivale edition of Sheraton Sunset Sessions.

World famous for celebrating spectacular sunsets in Ibiza since the 80’s, Café del Mar remains one of the Spanish island’s most treasured venues to this day. The true pioneers of bringing music and stellar vibes together with Mediterranean food and cool drinks, this special Café del Mar edition of Sheraton Sunset Sessions is sure to be a hot ticket during Port Douglas Carnivale 2024.

As the sun lowers in the sky on Saturday the 25th of May, Sheraton Grand Mirage Resort Port Douglas will come to life as colourful cocktails, Mediterranean bites and tunes by Cafe del Mar DJ ‘Jus Joe’ flow onto the shore of the resort’s Main Beach.

Choose from three fabulous entry choices– from the 'Private Cabana' package that offers day-use of a poolside cabana and an evening of French champagne and seafood, to the immersive ‘General Admission' ticket that includes $50 of food and drink credit to spend as you please.

Don’t miss out – limited tickets available!

WIN A TRIP TO VIVID SYDNEY! Every ticket holder goes into a draw to win a weekend for 2 during VIVID SYDNEY! The prize includes:

2 return Airfares from Cairns to Sydney*

2 nights accommodation at Sheraton Grand Sydney Hyde Park*

Lunch for 2 at Café Del Mar on Darling Harbour

|

Sheraton Grand Mirage Resort Port Douglas

|

From $50

|

https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/sheraton-sunset-session-x-cafe-del-mar-carnivale-edition-tickets-876411098187?aff=NPWhatsOn

| | |

Community Event, Food & Wine Event, Live Entertainment

| |

Alina Polishuk

|

[email protected]

|

0413357035

| |

| 7. |

Saturday 27 April 2024

2024-04-27T00:00:00+10:00

|

10 am

|

11 am

|

International tai chi and qi gong day

|

Saturday 27 April is international qi gong and tai chi day.

Several groups will come together in Mossman George Davis park (opposite the markets).

Tai chi and chi gong have a profound influence on both physical and mental health.

Everyone can learn it, come and see for yourself.

|

George Davis park

|

Free

| |

0488349713

|

[email protected]

|

Arts & Culture, Free Event, Senior Event, Sport Event

|

Please join us. Wear comfortable clothing and have water with you…

And a big smile

|

Frieda van Aller

|

[email protected]

|

0488349713

| |

| 8. |

Friday 3 May 2024

2024-05-03T00:00:00+10:00

|

7.00pm

|

Late

|

THE RUBENS @The Yachty

|

THE RUBENS launch their Black Balloon Tour right here in Port Douglas

|

Port Douglas Yacht Club

|

$55

|

portdouglasyachtclub.com.au

| | |

Arts & Culture, Community Event, Live Entertainment, Major Event

|

Tickets via OZTIX

|

Bruce Dargavel

|

[email protected]

|

0419009425

| |

| 9. |

Thursday 2 May 2024

2024-05-02T00:00:00+10:00

|

7PM

| |

TOPICS IN THE TROPICS - TRIVIA

|

Trivia's back at Hemingway's!

Every Thursday Night at starting at 7pm. Grab your fellow brainiacs for an evening of fun.

Come and enjoy dinner first (bookings from 6pm) or a few bevies while you give your brains a workout.

Bookings recommended.

|

Hemingways' Brewery

|

Free

|

https://www.hemingwaysbrewery.com/whats-on/all-events/topics-in-the-tropics-trivia#c1375

|

0482 173 337

|

[email protected]

|

Family Event, Free Event, Trivia & Games

| |

Kim

|

[email protected]

|

0438374860

| |

| 10. |

Wednesday 4 December 2024

2024-12-04T00:00:00+10:00

|

10 am

| |

Free Kids Fun Yoga & Mindfulness Playshop

|

School Holiday Kids Yoga for Primary School Aged Kids.

|

Port Douglas Neighborhood Center

|

free

|

https://www.trybooking.com/events/landing/1198069?

|

0438117486

|

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Family Event, Free Event, Sport Event, Workshop or Training

|

Bookings Essential via link

|

Petra

|

[email protected]

|

0438117486

| |

| 11. |

Sunday 12 May 2024

2024-05-12T00:00:00+10:00

|

8.30 AM

|

12.30 PM

|

Locals Retreat - Yoga Waterfall Hike

|

Invitation to a wholesome half a day with like minded souls and local community. Connect.

What to expect?

BREATHE ~ NATURE ~ YOGA ~ HUMAN EXPERIENCE ~ SWIM ~ PICNIC ~ MEDITATE ~ REPLENISH

I would love for you all to have a retreat experience, especially now before we all dive into busy months in Port Douglas.

|

Hartley's Creek Falls

|

50

|

https://yogainthetropics.com

|

0438117486

|

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Family Event, Live Entertainment, Major Event, Sport Event, Workshop or Training

|

locals only - Port Douglas, Mossman, Julatten, Palm Cove, Oak Beach, Cairns.

Tourist can book their experience - https://yogainthetropics.com/yoga-waterfall-hikes

|

Petra

|

[email protected]

|

0438117486

| |

| 12. |

Sunday 18 August 2024

2024-08-18T00:00:00+10:00

|

6:00am

|

4:00pm

|

60km K2PD SOLO and Team Relay foot race

|

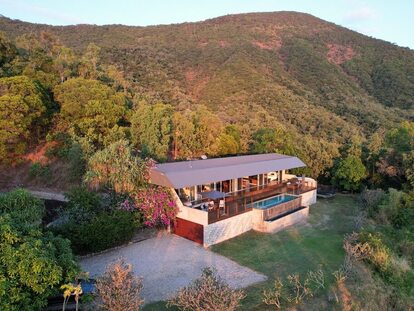

The Kuranda to Port Douglas is a point-to-point race incorporated in the Mowbray National Park within the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. It starts just off Kennedy Highway in Kuranda and follows Black Mountain Road through native rainforest, open eucalyptus forest, pine plantations and over picturesque creeks. The finish is on the famous Four Mile Beach, Port Douglas. The tropical rainforest is home to the endangered southern cassowary, a flightless bird that can grow to two metres in height - you might see one!

Join us for the 60km K2PD SOLO and Team Relay foot race. Entries close at 11.59pm, Thursday, 15 August 2024.

A medal is included in your entry fee.

|

Kuranda to Port Douglas

|

$100 for solo; $50 per team member. Early bird discounts apply.

|

https://www.racespace.com/au/dynamic-running-ltd/k2pd2024

|

0417798444

|

[email protected]

|

Sport Event

| |

Lorraine Lawson

|

[email protected]

|

0417798444

| |

| 13. |

Sunday 26 May 2024

2024-05-26T00:00:00+10:00

|

8:00am

|

9:00am

|

Douglas Dash

|

Distance: approximately 5km

Terrain: Beach sand and dirt track

Start: Four Mile Beach Park off Barrier Road, Port Douglas

Finish: Rex Smeal Park, Port Douglas

|

Four Mile Beach Park

|

$25.00 (adults) $15.00 (juniors)

|

https://www.racespace.com/au/dynamic-running-ltd/douglasdash2024

|

0417798444

|

[email protected]

|

Sport Event

| |

Lorraine Lawson

|

[email protected]

|

0417798444

| |

| 14. |

Sunday 2 June 2024

2024-06-02T00:00:00+10:00

|

9:45 am

|

11:15 am

|

I Believe I Can Fly - Yoga Arm Balance Workshop - Level 1

|

BELIEVE YOU CAN FLY, AND YOU ARE HALF WAY THERE.

The other half is my job - preparation body and mind, drills, poses, relaxation - zen in the soul.

Can’t wait to share the step by step how to fly. I invite you to join me for a fear conquering, yet fun workshop to feel amazing in your body.

Namaste Petra, Your Local Yoga Teacher

|

Port Douglas Yoga Studio - Level 1, Corner Warner St and Grant St

|

40

|

https://yogainthetropics.com/home

|

+61438117486

|

[email protected]

|

Community Event, Major Event, Workshop or Training

|

No Experience with yoga and arm balances required nor need to bring yoga mat.

24 hr cancelations policy

|

Petra

|

[email protected]

|

0438117486

| |