Running on a whim, and getting away with it

CRISPIN HULL COLUMN

You can do what you like unless there is a law to stop you. This might sound like a radical, right-wing, libertarian catch cry. But it is, in fact, the bedrock of a rule-of-law democratic society. It is the bedrock of freedom.

In a rule-of-law democracy, laws are made by elected representatives of the people. They are administered by a directly or indirectly elected executive which also has to obey the law. Any disputes about how the law is to be applied to individuals or circumstances are resolved by an independent judiciary.

In nations that are not rule-of-law democracies, the people get no say in the making of the law, the executive exercises power with little restraint, and there is no independent judiciary to say how and upon whom is the law to be applied.

Rule-of-law democracies provide certainty and liberty for their people.

It is worth restating these basic principles because events unfolding in the US now show us that the US is no longer a rule-of-law democracy.

The list of those events is getting longer. President Donald Trump ordered the vengeful prosecution of two officials (James Comey and Letitia James) who played roles in the investigation and successful prosecution of Trump himself when he was not president. Equally, Trump has ordered well-founded prosecutions against his allies be dropped. Trump has unilaterally imposed tariffs on nations he has a grievance with. He has withdrawn legally given government renewable-energy grants. He has reneged on security arrangements with key allies. He has abused government contracts to punish enemies and reward friends. He has sued people and businesses on flimsy grounds so they pay out the blackmail

It has profound implications for Australia. For the past 80 years Australia has based its national security around an alliance with the US based on “shared values”. The fundamental value, of course, is the liberty, freedom, and certainty that come with the rule of law in a democracy.

Trump, on the other hand, gains attention and power through chaos, volatility, and uncertainty – exactly the opposite of rule-of-law principles.

Trump’s actions instil fear into people so that they obey his every order or anticipate his every whim. It is rule by personality, not law.

(Comey, by the way, was the special prosecutor who investigated Russian links to Trump’s 2016 election campaign. And James was the New York Attorney General who secured Trump’s conviction for business malpractice.)

This rule by chaos and whim, however, is coming at a huge cost.

Business hates uncertainty and volatility which cause fear to overtake greed as the basis of business decisions. Businesses batten down and do not invest. Instead, they rush for gold and government bonds.

That is not good for employment or the economy in general.

Last week Trump posted just 500 words on his Truth Social platform to threaten a 100 percent extra tariff on Chinese goods because of China’s threatened restrictions on rare-earth exports. Immediately, the US share market dropped by $US2 trillion.

It was a crystalising example of the fundamental internal contradiction of the Trump presidency.

On one hand, Trump wants American business to succeed and be more profitable. But, on the other hand, he acts erratically day-to-day on his latest whim to punish anyone, any firm, or any nation that incurs his displeasure.

General economic uncertainty is bad enough, but if that is overlaid with political uncertainty created by personal whim exercising constitutionally dubious power, businesses will curtail investment.

Australia needs to look out. A little reported exchange at a US Senate committee hearing last week, gives us an inkling of what we might be in for.

Republican Senator Roger Wicker questioned Trump’s nominee for the position of Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs, John Noh, about the review of the AUKUS pact.

Wicker said the review came as a “surprise” to Congress and “our steadfast ally, Australia”.

Noh said he did not want to “get ahead” of Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Elbridge Colby, who is doing the review, but, “There are things that I believe are common sense, things that we can do to strengthen AUKUS, to strengthen Pillar I to ensure that it is more sustainable.”

Pillar I is the sale to Australia of three Virginia-class nuclear submarines which Trump has cast doubt upon. Noh’s statement came straight out of the Trump playbook: engender uncertainty and doubt, often using a proxy, and then renegotiate to make the other side pay more. And Australia has already paid $1.6 billion to the US.

That is how Trump looks at things: a zero-sum game in which even allies are “the other side” in a deal-making exercise.

Wicker also questioned the legality of Trump moving $US400 million in military aid to Taiwan from gift status to purchase status. Noh cited Trump’s desire to see allies pay for US weapons as the basis for the decision with no answer to Wicker’s legal question.

It would be dangerous for Australia to give in to a reworking of AUKUS. It would be a form of appeasement to authoritarianism. Similarly, handing the US some easy, cheap access to Australian rare-earth resources would also be a form of appeasement to authoritarianism.

Authoritarians work on the basis of not abiding by their word. If they renege once, they think they can renege again, and again, and again. They think they can extract undeserved advantage by threatening chaos and uncertainty.

Security alliances and international trade require certainty, reliability, and rules. Australia would do well to promote a security-trade alliance of rule-of-law democracies with objective criteria for joining. At present, the US would not qualify.

The question now for Australia is do we hold our breath for the next three and bit years and hope for a return to normalcy. Or do we say that is too risky. After all, reversing authoritarian tendencies has not been the trend of 21 st century politics. To the contrary.

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 14 October 2025.

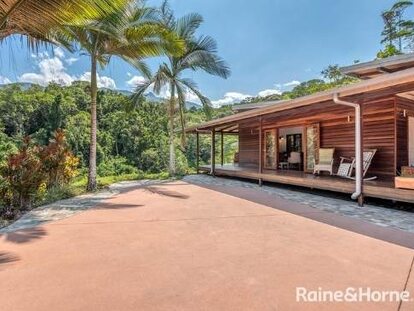

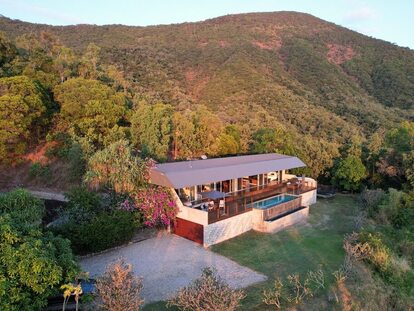

*Crispin Hull is a distinguished journalist and former Editor of the Canberra Times. In semi-retirement, he and his wife live in Port Douglas, and he contributes his weekly column to Newsport pro bono.

- The opinions and views in this column are those of the author and author only and do not reflect the Newsport editor or staff.

Support public interest journalism

Help us to continue covering local stories that matter. Please consider supporting below.